Storzapretti are Corsican dumplings made with spinach or chard and cheese, topped with tomato sauce and more cheese, and baked until bubbly and golden. According to legend, a priest once found the dumplings so delicious that he stuffed himself to the point of choking, hence their name, which translates roughly as ‘strangle the preacher’. One might think they’d be heavy, but after eating a plateful my guest pronounced them delightfully light.

Storzapretti are Corsican dumplings made with spinach or chard and cheese, topped with tomato sauce and more cheese, and baked until bubbly and golden. According to legend, a priest once found the dumplings so delicious that he stuffed himself to the point of choking, hence their name, which translates roughly as ‘strangle the preacher’. One might think they’d be heavy, but after eating a plateful my guest pronounced them delightfully light.

Storzapretti / Corsican dumplings in tomato sauce

I stumbled upon this recipe during a recent trip to Corsica, known by the French as l’Île de Beauté (the Isle of Beauty). And it is incredibly beautiful. White sand beaches, pale turquoise waters, charming villages nestled in mountains rising just inland from the sea, parasol pines, flowers everywhere. Seafood is plentiful, the veggies are gorgeous and local specialties include brocciu, a fresh cheese similar to ricotta made of sheep or goats milk.

One of the island’s signature dishes is cannelloni au brocciu, in which the tubular cannelloni are stuffed with a mixture of brocciu and Swiss chard. Storzapretti are like cannelloni au brocciu minus the cannelloni. There is a bit of potato, making them somewhat akin to gnocchi, but they are far lighter and fluffier. As brocciu can be hard to find outside Corsica, and even in Corsica has a season, ricotta may be used instead.

Upon returning from Corsica I did a little research and discovered that the dumplings have roots in the Trentino region of Italy (and, as my Italian friends like to point out, Corsica was ruled by the Italians long before it became part of France). I also discovered that, within Corsica, the dish is a regional specialty, the region being the north of the island and in particular the area around the city of Bastia. When I asked a Corsican friend about the dish, she’d never heard of it — her family’s place is further south.

The name itself is problematic. According to Laure Verdeau, whose grandmother was from Bastia and who wrote about storzapretti recently for M, the magazine of Le Monde, the name translates from Corsican into French as étouffe-prêtre, or ‘choke the priest’. Other sources translate the name as tordre le moine (‘twist the monk’) or presser le moine (‘squeeze the monk’). But if etymology can be a guide, then the Italian version, strangolapreti, resolves the argument. It very clearly means ‘priest stranglers’.

The Italian dish differs from the Corsican version, however. My favorite Italian recipe site describes strangolapreti as ‘a truly ancient dish of truly special gnocchi made with stale bread and spinach’. No potato and no fresh cheese. The herbs are also different. The Corsican dumplings are flavored with mint and parsley, the Italian with fresh sage. And the Italian dumplings are served with melted butter — no tomato sauce involved.

This being said, the cooking of the dumplings is similar. You make a batter, form oval shapes, dust them with flour and drop them into boiling water until they fluff up and rise to the surface. This is the fun part of the recipe, which is admittedly a bit more of a production than most of the recipes on this site. But you can do it in stages, for example by making the tomato sauce the day before embarking on the dumplings themselves.

The storzapretti may be served either as a vegetarian main course or starter, or as a side dish with grilled or roasted meat, fish or poultry. You could begin with, say, melon and prosciutto and follow up with fresh summer fruit or a fruity dessert. Either a chilled rosé or a dry red would marry well. You might just feel like you’re on a beautiful island…

Happy cooking.

Italian-style sausages marry beautifully with finocchio, aka fennel, in this one-dish meal for all seasons. It’s a crowd pleaser that also includes potatoes, and you can round out the dish with a seasonal veggie — e.g. peas in springtime, butternut in the fall. Here in France I used the readily available saucisses de Toulouse, which like Italian sausages are about 1 inch (2.5 cm) in diameter. But it could be argued that the Italian variety is better.

Italian-style sausages marry beautifully with finocchio, aka fennel, in this one-dish meal for all seasons. It’s a crowd pleaser that also includes potatoes, and you can round out the dish with a seasonal veggie — e.g. peas in springtime, butternut in the fall. Here in France I used the readily available saucisses de Toulouse, which like Italian sausages are about 1 inch (2.5 cm) in diameter. But it could be argued that the Italian variety is better. If you’ve ever been to Nice, you will have encountered the pan bagnat, that city’s trademark sandwich: a large roll stuffed with tuna, tomatoes, black olives, hard-boiled egg, anchovies, green pepper, green onion, radishes and basil. It’s like a

If you’ve ever been to Nice, you will have encountered the pan bagnat, that city’s trademark sandwich: a large roll stuffed with tuna, tomatoes, black olives, hard-boiled egg, anchovies, green pepper, green onion, radishes and basil. It’s like a  Happily I phoned ahead, as the pan bagnat rolls had to be made to order. The next day I collected four beautiful crusty rolls. The rest was easy. I made a sauce of olive oil, garlic and basil, boiled an egg, sliced the veggies, sliced the roll and layered on the ingredients, drizzing with olive oil from time to time. In a very short while the venerable sandwich was ready.

Happily I phoned ahead, as the pan bagnat rolls had to be made to order. The next day I collected four beautiful crusty rolls. The rest was easy. I made a sauce of olive oil, garlic and basil, boiled an egg, sliced the veggies, sliced the roll and layered on the ingredients, drizzing with olive oil from time to time. In a very short while the venerable sandwich was ready. What better time than spring to make fresh spring rolls? In this Vietnamese-inspired recipe, a very thin rice-flour crepe is rolled up around lettuce, mint and the zesty filling of your choice: shrimp, chicken or mango, mixed with Asian flavorings, peanuts and cilantro. The rolls — not to be confused with fried spring rolls (called nems in France) — are served with a tangy sauce. They’re light, fun to make and a great way to exercise your creativity.

What better time than spring to make fresh spring rolls? In this Vietnamese-inspired recipe, a very thin rice-flour crepe is rolled up around lettuce, mint and the zesty filling of your choice: shrimp, chicken or mango, mixed with Asian flavorings, peanuts and cilantro. The rolls — not to be confused with fried spring rolls (called nems in France) — are served with a tangy sauce. They’re light, fun to make and a great way to exercise your creativity. When you’re ready to roll, the rice-flour wrapper is dampened in hot water, then placed on a board. Lettuce and mint are placed on the bottom third and topped with a couple spoonfuls of filling. Shrimp halves are then placed on the middle of the wrapper. You fold in the sides and wrap up tightly, bottom to top. If making the vegetarian/vegan mango version, you can skip the shrimp and instead use cilantro leaves for decoration.

When you’re ready to roll, the rice-flour wrapper is dampened in hot water, then placed on a board. Lettuce and mint are placed on the bottom third and topped with a couple spoonfuls of filling. Shrimp halves are then placed on the middle of the wrapper. You fold in the sides and wrap up tightly, bottom to top. If making the vegetarian/vegan mango version, you can skip the shrimp and instead use cilantro leaves for decoration. Is there such a thing as a new recipe? This zesty salad of watercress topped with anchovy fillets and croutons may fit the bill. I created it one day when I’d been to the market and had a bunch of fresh watercress in the fridge. How was I inspired to add the anchovies and croutons, along with a drizzle of olive oil and a few drops of lemon juice? Don’t know, but when I surfed the web afterwards in search of a similar salad, I found none.

Is there such a thing as a new recipe? This zesty salad of watercress topped with anchovy fillets and croutons may fit the bill. I created it one day when I’d been to the market and had a bunch of fresh watercress in the fridge. How was I inspired to add the anchovies and croutons, along with a drizzle of olive oil and a few drops of lemon juice? Don’t know, but when I surfed the web afterwards in search of a similar salad, I found none. A swirl of lightened mayo over gently steamed carrots, asparagus, peas, spring onions and turnips creates a thoroughly modern version of a very traditional French dish — macédoine. In this update, the veggies may be served either chopped or whole, with homemade mayonnaise on top, on the side or as a sauce. Add some fresh herbs for garnish, and you have a flavor-packed starter, salad or side dish that highlights the beauty of spring.

A swirl of lightened mayo over gently steamed carrots, asparagus, peas, spring onions and turnips creates a thoroughly modern version of a very traditional French dish — macédoine. In this update, the veggies may be served either chopped or whole, with homemade mayonnaise on top, on the side or as a sauce. Add some fresh herbs for garnish, and you have a flavor-packed starter, salad or side dish that highlights the beauty of spring. So I have taken liberties with the traditional recipe, which typically combined diced carrots, green beans, turnips, peas and flageolets, or small, pale green, kidney-shaped beans that are popular in France but may be hard to find elsewhere. This version dispenses with the beans in favor of asparagus and spring onions, which are bountiful in farmers markets here at the moment.

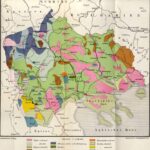

So I have taken liberties with the traditional recipe, which typically combined diced carrots, green beans, turnips, peas and flageolets, or small, pale green, kidney-shaped beans that are popular in France but may be hard to find elsewhere. This version dispenses with the beans in favor of asparagus and spring onions, which are bountiful in farmers markets here at the moment. It may be argued that serving the veggies whole, as shown just above, is too much of a stretch, given the origins of the dish. Amusingly, macédoine takes its name from the multiethnic Balkan region of Macedonia. The multicolored chopped vegetables were seen as resembling ethnographic maps of Macedonia in previous centuries, such as the one at left.

It may be argued that serving the veggies whole, as shown just above, is too much of a stretch, given the origins of the dish. Amusingly, macédoine takes its name from the multiethnic Balkan region of Macedonia. The multicolored chopped vegetables were seen as resembling ethnographic maps of Macedonia in previous centuries, such as the one at left. As for the veggie version, macédoine-style chopped vegetables may also be served warm with butter or cold in aspic, according to the Larousse Gastronomique. But personally I think the mayo version is by far the tastiest. If you’d like to go traditional, you can served your modernized macédoine bathed in homemade mayonnaise lightened with lemon juice, as shown at right. Or you can decompose and recompose as you prefer.

As for the veggie version, macédoine-style chopped vegetables may also be served warm with butter or cold in aspic, according to the Larousse Gastronomique. But personally I think the mayo version is by far the tastiest. If you’d like to go traditional, you can served your modernized macédoine bathed in homemade mayonnaise lightened with lemon juice, as shown at right. Or you can decompose and recompose as you prefer. Spring has sprung with a vengeance in Paris — chestnuts in blossom, demonstrators in the streets — meaning it’s time once again for Crème de la crème, with ‘best of’ seasonal recipes from the first ten years of The Everyday French Chef. This time I’d like to highlight oeufs durs mayonnaise, a classic bistro dish. And, you may well ask, what’s so special about hard-boiled eggs? Well, homemade mayo boosts this simple dish into the stratosphere.

Spring has sprung with a vengeance in Paris — chestnuts in blossom, demonstrators in the streets — meaning it’s time once again for Crème de la crème, with ‘best of’ seasonal recipes from the first ten years of The Everyday French Chef. This time I’d like to highlight oeufs durs mayonnaise, a classic bistro dish. And, you may well ask, what’s so special about hard-boiled eggs? Well, homemade mayo boosts this simple dish into the stratosphere. Starters

Starters Soups

Soups Salads

Salads Eggs

Eggs Savory tarts

Savory tarts Fish

Fish

Meat

Meat Veggies

Veggies Pasta and grains

Pasta and grains Desserts

Desserts Here’s a cake that’s both Moorish and ‘more-ish’. Moorish because its ground walnuts and almonds, orange zest, cinnamon and rose water are evocative of North African cuisine. More-ish because, as I discovered when I served it this week, one serving was not enough for the guests around my table. This cake is also unusual because it contains no flour. That makes it both gluten-free and ideal for serving during the Jewish holiday of Passover.

Here’s a cake that’s both Moorish and ‘more-ish’. Moorish because its ground walnuts and almonds, orange zest, cinnamon and rose water are evocative of North African cuisine. More-ish because, as I discovered when I served it this week, one serving was not enough for the guests around my table. This cake is also unusual because it contains no flour. That makes it both gluten-free and ideal for serving during the Jewish holiday of Passover. This fish dish with a crusty topping is extremely popular in France and a breeze to make. The topping ‘à la bordelaise‘ — literally Bordeaux style — combines breadcrumbs, shallots, garlic, parsley, salt, pepper, olive oil, lemon and a splash of white wine. Cod or hake are often used, but in fact any white-fleshed fish is fine. The upshot is a sophisticated French take on breaded fish. But does this family friendly dish actually hail from Bordeaux?

This fish dish with a crusty topping is extremely popular in France and a breeze to make. The topping ‘à la bordelaise‘ — literally Bordeaux style — combines breadcrumbs, shallots, garlic, parsley, salt, pepper, olive oil, lemon and a splash of white wine. Cod or hake are often used, but in fact any white-fleshed fish is fine. The upshot is a sophisticated French take on breaded fish. But does this family friendly dish actually hail from Bordeaux? Then I discovered thanks to ‘pingbacks’ that my site was being pirated. It wasn’t the first time this has happened, but after I posted my last recipe, for

Then I discovered thanks to ‘pingbacks’ that my site was being pirated. It wasn’t the first time this has happened, but after I posted my last recipe, for  Meantime the people who pirate my site are publishing ads, which I decided from the outset not to do in order to keep the site reader friendly — although I am solicited several times each week by people wanting to advertise or publish sponsored content on my site. Thus the pirates are not just committing theft of intellectual property but also making money from my work, and there doesn’t seem to be anything I can do about it. If anyone has a recipe for putting an end to this situation, please let me know. Nonetheless…

Meantime the people who pirate my site are publishing ads, which I decided from the outset not to do in order to keep the site reader friendly — although I am solicited several times each week by people wanting to advertise or publish sponsored content on my site. Thus the pirates are not just committing theft of intellectual property but also making money from my work, and there doesn’t seem to be anything I can do about it. If anyone has a recipe for putting an end to this situation, please let me know. Nonetheless… Basil hummus? Why not? I discovered this recipe thanks to my friend Yana, a Ukrainian artist who’s lived in Paris for the last 30 years. What she makes is idiosyncratic, often with an artist’s touch. Her anchovy dip is fantastic, but when I discovered that it involved nothing but anchovies and pure butter, I gasped at how much I’d consumed. The basil hummus is lighter. She served it on a summer’s evening, with basil plucked from her garden.

Basil hummus? Why not? I discovered this recipe thanks to my friend Yana, a Ukrainian artist who’s lived in Paris for the last 30 years. What she makes is idiosyncratic, often with an artist’s touch. Her anchovy dip is fantastic, but when I discovered that it involved nothing but anchovies and pure butter, I gasped at how much I’d consumed. The basil hummus is lighter. She served it on a summer’s evening, with basil plucked from her garden. Meantime I have updated The Everyday French Chef’s

Meantime I have updated The Everyday French Chef’s  Happy cooking.

Happy cooking.