I tried this clam chowder at the Hog Island Oyster Co. in Napa, California, and when I finished it I knew I needed the recipe. What I didn’t know is that chowder, an American dish, has French roots — or that the word ‘chowder’ derives from the French chaudrée, meaning cauldron. This I discovered upon my return to Paris. I quickly went out and bought the ingredients — clams, potatoes, leek, celery, carrot, bacon and heavy cream.

I tried this clam chowder at the Hog Island Oyster Co. in Napa, California, and when I finished it I knew I needed the recipe. What I didn’t know is that chowder, an American dish, has French roots — or that the word ‘chowder’ derives from the French chaudrée, meaning cauldron. This I discovered upon my return to Paris. I quickly went out and bought the ingredients — clams, potatoes, leek, celery, carrot, bacon and heavy cream.

Chaudrée de palourdes / Clam chowder

The recipe is easy and takes about half an hour to prepare. The key to success is to use the small, sweet clams known as palourdes in French, Manila clams or steamers in English, and vongole in Italian. The clams should be as fresh as possible — at Hog Island Oyster Co., where I lunched with my cousin Paul on a cold, wet January afternoon, we were told that the clams had been fished out of a nearby bay that very morning.

The recipe is easy and takes about half an hour to prepare. The key to success is to use the small, sweet clams known as palourdes in French, Manila clams or steamers in English, and vongole in Italian. The clams should be as fresh as possible — at Hog Island Oyster Co., where I lunched with my cousin Paul on a cold, wet January afternoon, we were told that the clams had been fished out of a nearby bay that very morning.

That was one reason our lunch was so memorable. The other was the oysters we had as a starter. As reluctant as I may be to say so, those oysters were better than any I’ve had in France — or anywhere else for that matter. They were small but deep, succulent and nutty. A crisp Chardonnay grown on the surrounding vines in Napa completed the picture.

I spent three weeks in California over the new year, mainly in the Bay Area, and from a foodie point of view the trip held other surprises. The most startling thing was the prices. On the night I arrived, I went out with a friend to a laid-back joint in Oakland where two bacon cheeseburgers, two glasses of red and a glass of sparkling water cost … $80. About double what it would cost in Paris. Likewise, at a bakery in San Diego, three cups of soup, a turkey sandwich and a plate of potato chips set my cousin Janice back $80. But that was nothing compared to my bill of $150 for lunch for two at a Greek place in San Francisco.

Or the eye-popping $700 bill for dinner for four at a high-end Chinese, where the creative five-course fixed-price menu ($90 per person not counting drinks, dessert, tax or tip) included a starter of ‘Winter Perigord Truffle Puff’, ‘Chilled Fresh Lily Bulb’ and ‘Scallop and Caviar Roll’ (at left). Okay, the view was fantastic and the ambiance refined, and the cost wasn’t an issue for me as I was generously treated by my brother and sister-in-law. But it made me realize that, although Paris is reputedly one of the world’s most expensive cities, one can dine out, well, for far less.

Or the eye-popping $700 bill for dinner for four at a high-end Chinese, where the creative five-course fixed-price menu ($90 per person not counting drinks, dessert, tax or tip) included a starter of ‘Winter Perigord Truffle Puff’, ‘Chilled Fresh Lily Bulb’ and ‘Scallop and Caviar Roll’ (at left). Okay, the view was fantastic and the ambiance refined, and the cost wasn’t an issue for me as I was generously treated by my brother and sister-in-law. But it made me realize that, although Paris is reputedly one of the world’s most expensive cities, one can dine out, well, for far less.

Getting back to chowder, it is said to have originated on the Atlantic coast of France, where la chaudrée is a soup of fish and shellfish cooked with veggies, bacon, white wine and cream. According to lore, French immigrants enjoyed what was to become known as chowder while sailing to the United States and Canada in the 17th century. It put down roots first as New England clam chowder, similar to today’s recipe, and later as Manhattan clam chowder, made with a tomato broth and no cream.

Despite its French roots, clam chowder is not served in restaurants in Paris — at least, in my nearly 50 years here, I’ve never encountered it. Which means that in order to enjoy this warming, ultraflavorful soup, you need to go hunting for clams. This I did at my local farmers market, where various types of clams — including two sorts of palourdes, small and large — were on sale on a recent Sunday. If fresh clams aren’t available where you live, you can buy them online in the States or in the UK.

Despite its French roots, clam chowder is not served in restaurants in Paris — at least, in my nearly 50 years here, I’ve never encountered it. Which means that in order to enjoy this warming, ultraflavorful soup, you need to go hunting for clams. This I did at my local farmers market, where various types of clams — including two sorts of palourdes, small and large — were on sale on a recent Sunday. If fresh clams aren’t available where you live, you can buy them online in the States or in the UK.

Happy cooking.

I discovered spinach risotto many years ago at a dinner party in Venice. Our host, a genial fellow named Giorgio, was chatting me up, so I followed him into the kitchen and watched as he chopped and sautéd and ladled and stirred. Distracted by his charm, I didn’t know what he was making until he brought the dish to the table. ‘Risotto agli spinaci’, he announced with a flourish. One earthy, creamy, tangy mouthful and I was in heaven. Pure bliss.

I discovered spinach risotto many years ago at a dinner party in Venice. Our host, a genial fellow named Giorgio, was chatting me up, so I followed him into the kitchen and watched as he chopped and sautéd and ladled and stirred. Distracted by his charm, I didn’t know what he was making until he brought the dish to the table. ‘Risotto agli spinaci’, he announced with a flourish. One earthy, creamy, tangy mouthful and I was in heaven. Pure bliss. The French love stuffed cabbage in winter. They serve it two ways — with meatballs rolled up in individual cabbage leaves and, impressively, as a reconstituted whole cabbage with the stuffing inserted between the leaves. This recipe, which uses the far easier first method, puts a French twist on a dish my grandmother used to serve, with flavors redolent of her Jewish Ukrainian roots.

The French love stuffed cabbage in winter. They serve it two ways — with meatballs rolled up in individual cabbage leaves and, impressively, as a reconstituted whole cabbage with the stuffing inserted between the leaves. This recipe, which uses the far easier first method, puts a French twist on a dish my grandmother used to serve, with flavors redolent of her Jewish Ukrainian roots. Winter’s here, bring on the comfort food! This is the second chapter of ‘Crème de la crème’, a seasonal feature marking the tenth anniversary of The Everyday French Chef. On the menu are my favorite winter recipes (not including holiday recipes — if you’re still thinking about what to serve on Christmas or New Year’s, click

Winter’s here, bring on the comfort food! This is the second chapter of ‘Crème de la crème’, a seasonal feature marking the tenth anniversary of The Everyday French Chef. On the menu are my favorite winter recipes (not including holiday recipes — if you’re still thinking about what to serve on Christmas or New Year’s, click  Starters

Starters Soups

Soups Salads

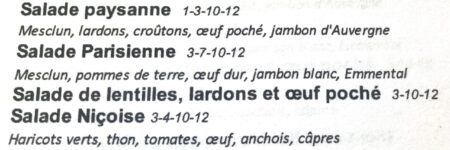

Salads

Savory tarts and sandwiches

Savory tarts and sandwiches Fish and shellfish

Fish and shellfish

Meat dishes

Meat dishes

Pasta and grains

Pasta and grains Desserts

Desserts It’s no secret that a highlight of French Christmas is the bûche de Noël that crowns a festive meal. What is less well known is that the traditional Yule log cake is rarely — but I mean, really rarely — made at home in France. This is because prettily decorated bûches in all sizes are on offer at every pastry shop in the country during the season. And yet, as I discovered in my kitchen, it’s both possible and amusing to make one yourself.

It’s no secret that a highlight of French Christmas is the bûche de Noël that crowns a festive meal. What is less well known is that the traditional Yule log cake is rarely — but I mean, really rarely — made at home in France. This is because prettily decorated bûches in all sizes are on offer at every pastry shop in the country during the season. And yet, as I discovered in my kitchen, it’s both possible and amusing to make one yourself. Duck has always been a big deal in France, culinarily speaking, and what with the popularity of a certain American import it was inevitable that the French would put their own twist on it and create the duck burger. Some recipes use

Duck has always been a big deal in France, culinarily speaking, and what with the popularity of a certain American import it was inevitable that the French would put their own twist on it and create the duck burger. Some recipes use  Many years ago, when making boeuf bourguinon for a party, I discovered a sophisticated side dish with laughably humble origins — cabbage purée. How I discovered it is a mystery. I thought it might have been via Patricia Wells, but when I looked through her cookbooks it wasn’t there. Perhaps it was Julia Child? Negative. Well, whatever. I’ve been making it for years, and am always delighted when my guests can’t figure out what it is.

Many years ago, when making boeuf bourguinon for a party, I discovered a sophisticated side dish with laughably humble origins — cabbage purée. How I discovered it is a mystery. I thought it might have been via Patricia Wells, but when I looked through her cookbooks it wasn’t there. Perhaps it was Julia Child? Negative. Well, whatever. I’ve been making it for years, and am always delighted when my guests can’t figure out what it is. This savory pie of chicken, mushrooms and leeks in a creamy sauce encased in puff pastry (pâte feuilletée) makes a lovely autumn dish for lunch or a light supper. Full disclosure: I don’t make the pastry myself, but instead use a couple rolls of high-quality, all-butter store-bought puff pastry. This saves a lot of time. Then all you need to do is invite a couple of guests, make a salad, open a bottle of wine and voilà — your meal is ready.

This savory pie of chicken, mushrooms and leeks in a creamy sauce encased in puff pastry (pâte feuilletée) makes a lovely autumn dish for lunch or a light supper. Full disclosure: I don’t make the pastry myself, but instead use a couple rolls of high-quality, all-butter store-bought puff pastry. This saves a lot of time. Then all you need to do is invite a couple of guests, make a salad, open a bottle of wine and voilà — your meal is ready. To allow steam to escape while the pie is baking, the French often cut a coin-shaped round out of the center of the top crust and insert a rolled piece of paper to create a chimney (cheminée). But I chose instead to cut a few slits into the top and, with leftover pâte feuilletée, added some cut-out diamonds for decoration. No sooner did the pie come out of the oven than it disappeared.

To allow steam to escape while the pie is baking, the French often cut a coin-shaped round out of the center of the top crust and insert a rolled piece of paper to create a chimney (cheminée). But I chose instead to cut a few slits into the top and, with leftover pâte feuilletée, added some cut-out diamonds for decoration. No sooner did the pie come out of the oven than it disappeared. This salad is a Paris bistro classic — tender leaves bathed in a light mustard vinaigrette and topped with cubed ham and cheese, boiled potatoes and quartered eggs. Or with other ingredients. Green beans, tomatoes, mushrooms, croutons, you name it. It’s a salad I’ve never encountered in a Parisian home, yet it is omnipresent in Paris cafés. I’ve put off posting about it for years for the simple reason that no one can agree on what it actually is.

This salad is a Paris bistro classic — tender leaves bathed in a light mustard vinaigrette and topped with cubed ham and cheese, boiled potatoes and quartered eggs. Or with other ingredients. Green beans, tomatoes, mushrooms, croutons, you name it. It’s a salad I’ve never encountered in a Parisian home, yet it is omnipresent in Paris cafés. I’ve put off posting about it for years for the simple reason that no one can agree on what it actually is.

For a supremely elegant brunch dish, you can’t do better than scrambled eggs with truffles. Wait! Did she say truffles? But yes, my friends. You may have heard that truffles cost as much per ounce as gold, but that turns out to be false. You may think they’re hard to find, but that’s also not true in these days of online ordering. Preserved truffles are fine in this quick and easy recipe. So go ahead — invite some guests and knock their socks off.

For a supremely elegant brunch dish, you can’t do better than scrambled eggs with truffles. Wait! Did she say truffles? But yes, my friends. You may have heard that truffles cost as much per ounce as gold, but that turns out to be false. You may think they’re hard to find, but that’s also not true in these days of online ordering. Preserved truffles are fine in this quick and easy recipe. So go ahead — invite some guests and knock their socks off. I’d been wanting to make scrambled eggs with truffles for a very long time, but when I went to my local farmers market recently in search of a truffle I couldn’t find one. Turns out they’re not in season. The season for the prized French black winter truffle begins only in mid-November, while the season for summer truffles ends in mid-September. But a shop in my neighborhood,

I’d been wanting to make scrambled eggs with truffles for a very long time, but when I went to my local farmers market recently in search of a truffle I couldn’t find one. Turns out they’re not in season. The season for the prized French black winter truffle begins only in mid-November, while the season for summer truffles ends in mid-September. But a shop in my neighborhood,  At last it’s time to make the eggs. This takes about three minutes. Slice the truffle thinly, reserve a few slices for garnish, beat the eggs with the cream, salt and pepper, and add the truffle slices. But how to cook them? The French method involves stirring the eggs into a creamy mass in a pan set over boiling water (au bain marie). But this is not strictly necessary. You can also scramble them as usual in a pan coated with melted butter.

At last it’s time to make the eggs. This takes about three minutes. Slice the truffle thinly, reserve a few slices for garnish, beat the eggs with the cream, salt and pepper, and add the truffle slices. But how to cook them? The French method involves stirring the eggs into a creamy mass in a pan set over boiling water (au bain marie). But this is not strictly necessary. You can also scramble them as usual in a pan coated with melted butter.